Chinese Medical Sciences Journal ›› 2022, Vol. 37 ›› Issue (1): 23-30.doi: 10.24920/003982

嗅觉缺失的新冠肺炎患者嗅球的磁共振成像结果:系统综述

阿泰菲•贝吉•霍扎尼1,阿米尔穆罕默德•梅拉吉哈2,*( ),马赫迪耶•苏莱曼尼3

),马赫迪耶•苏莱曼尼3

- 1伊朗医科大学外科系,德黑兰,伊朗

2萨布泽尔医科大学外科系,霍拉桑拉扎维省,伊朗

3马拉赫医科大学外科系,东阿塞拜疆省,伊朗

-

收稿日期:2021-08-14接受日期:2021-10-15出版日期:2022-03-31发布日期:2022-03-07 -

通讯作者:阿米尔穆罕默德•梅拉吉哈 E-mail:amir.meraj74@gmail.com

Magnetic Resonance Imaging Findings of Olfactory Bulb in Anosmic Patients with COVID-19: A Systematic Review

Atefeh Beigi-khoozani1,Amirmohammad Merajikhah2,*( ),Mahdieh Soleimani3

),Mahdieh Soleimani3

- 1Department of Operating Room, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2Department of Operating Room, Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences, Razavi Khorasan, Iran

3Department of Operating Room, Maragheh University of Medical Sciences, East Azerbaijan, Iran

-

Received:2021-08-14Accepted:2021-10-15Published:2022-03-31Online:2022-03-07 -

Contact:Amirmohammad Merajikhah E-mail:amir.meraj74@gmail.com

摘要:

背景 嗅觉缺失是新冠病毒(SARS-CoV-2)感染者的症状之一。在嗅觉缺失患者中,SARS-CoV-2可暂时改变嗅觉神经细胞和嗅球(OB)的信号传导过程,最终损害嗅觉上皮的结构,导致嗅觉通道的永久性紊乱。这种受损结构可在磁共振成像(MRI)中显示。

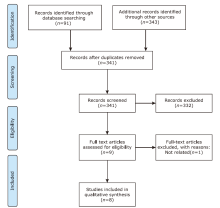

方法 两名研究人员独立搜索了四个数据库,包括PubMed、ProQuest、Scopus和Web of Science,以检索截至2020年11月11日的相关记录。检索不限时间、空间和语言。同时也检索了Google Scholar,但仅限于2020年的数据。根据PRISMA流程图对所有发现的文章进行了系统综述。定性研究、病例报告、社论、读者来信和其他非原创研究被排除在本系统分析之外。

结果 初步检索出434条记录。在查阅了标题和摘要后,选出74篇文章;最后,对8篇文章进行了全文审阅。结果显示在新冠肺炎患者可见嗅裂(OC)宽度和体积增加、OC完全或部分破坏以及OC完全阻塞。OB存在明显的变形和退化,并有细微的不对称。在这些研究中,计算机断层扫描(CT)、MRI和正电子发射断层扫描(PET)用于检测嗅觉缺失的结果。

结论 新冠肺炎患者OC的变化大于OB,主要是由于OC的炎症反应和免疫反应。然而,由神经或血管疾病所致的OB变化较少见。局部类固醇治疗和局部生理盐水可能有益。

引用本文

Atefeh Beigi-khoozani, Amirmohammad Merajikhah, Mahdieh Soleimani. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Findings of Olfactory Bulb in Anosmic Patients with COVID-19: A Systematic Review[J].Chinese Medical Sciences Journal, 2022, 37(1): 23-30.

"

| References | Study type | Number of patients | Cause of OD | Assessment | MRI manifestations | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odor assessment | Imaging modality | Olfactory cleft (OC) | Olfactory bulb (OB) | |||||

| Klironomos S, et al[ | Retrospective cohort study | 185 | SARS-CoV-2 infection | RT-PCR | CT and MRI | None | Abnormal OB signals | |

| Altundag A, et al[ | Prospective | 91 | SARS-CoV-2 infection; Non-SARS-CoV-2 infection | RT-PCR; Sniffin’ sticks test | CT and MRI | Increased widths and volume of OC | No significant difference in OB volumes and olfactory sulcus depths on MRI among anosmic patients | |

| Eliezer M, et al[ | Prospective case-controlled | 20 | SARS-CoV-2 infection | PCR; Visual Olfactive Score (VOS) | MRI | Complete obstruction of the OC occured in 95% of patients at the early stage; no obstruction was seen was seen during the 1-month follow-up | On the first MRI session, no significant difference in OB volume. At the 1-month follow-up visit, no significant difference in OB volume. Normal morphology of the OB | |

| Niesen M, et al[ | Prospective | 12 | SARS-CoV-2 infection | RT-PCR | PET; MRI with fluorodeoxyglucose | Bilateral obliteration of the OC in 50% of patients | Subtle asymmetry in OB | |

| Kandemirli SG, et al[ | Prospective | 23 | COVID-19 | PCR; Sniffin’ sticks test | CT; MRI | High rate of OC opacification | Reduction in OB volume; altered OB shape; signal abnormalities | |

| Aragão MFVV, et al[ | Retrospective | 5 | SARS-CoV-2 infection | Not performed | MRI with contrast enhancement | None | Abnormal OB intensities in all patients | |

| Brookes N, et al[ | Case series | 4 | COVID-19 | University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT) | MRI | None | In two cases, MRI showed normal OB and cribriform plates, along with minimal mucosal thickening in the ethmoid sinuses. | |

| Coolen T, et al[ | Prospective, case series | 19 | SARS-CoV-2 infection | PCR; chest CT | MRI and PET | Asymmetric olfactory bulb was observed, with or without obliteration of OC. Obliteration of OC and ipsilateral inflammation of OB | Asymmetric OB, inflation of OB | |

"

| Result of G immunoglobulin | Duration of effectiveness | Recovery time | Route of administration | Medicines in treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Partial | ||||

| Positive | 7 days | 2 - 3 weeks | 1 week (40% - 85%) | Oral | Steroids |

| Positive | 7 days | 2 - 3 weeks | 1 week (40% - 85%) | Local | Steroid drops |

| Positive | 3 days | 2 weeks | 1 week (85%) | Local | Ephedrine |

| Positive | 3 days | 2 weeks | 1 week (85%) | Local | Betnesol |

| Positive | 3 days | 2 weeks | 6 days | Oral | Prednisolone |

| None | 8 days | 2 weeks | 8 days | Local | Nasal saline irrigations |

| 1. |

Wu YC, Chen CS, Chan YJ. The outbreak of COVID-19: An overview. Chin Med Associat 2020; 83(3):217-20. doi: 10.1097/jcma.0000000000000270.

doi: 10.1097/jcma.0000000000000270 |

| 2. | World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 11 March 2020. Available from https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19-11-march-2020. Accessed March 5, 2021. |

| 3. |

Struyf T, Deeks JJ, Dinnes J, et al. Signs and symptoms to determine if a patient presenting in primary care or hospital outpatient settings has COVID-19 disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020; 7(7):CD013665. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013665.

doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013665 |

| 4. |

Rocke J, Hopkins C, Philpott C, et al. Is loss of sense of smell a diagnostic marker in COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clini Otolaryngol 2020; 45(6):914-22. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/coa.13620.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/coa.13620 |

| 5. | Hopkins C, Kumar N. Loss of sense of smell as marker of COVID-19 infection. The Royal College of Surgeons of England: British Rhinological Society 2020. http://www.entuk.com/_userfiles/pages/files/loss_of_sense_of_Smell-_as_marker_of_covid.pdf |

| 6. |

Tong JY, Wong A, Zhu D, et al. The prevalence of olfactory and gustatory dysfunction in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery 2020; 163(1):3-11. doi: 10.1177/0194599820926473.

doi: 10.1177/0194599820926473 |

| 7. |

Al-Ani RM, Acharya D. Prevalence of anosmia and ageusia in patients with COVID-19 at a primary health center, Doha, Qatar. Ind J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2020; 1-7. doi: 10.1007/s12070-020-02064-9.

doi: 10.1007/s12070-020-02064-9 |

| 8. |

Mishra P, Gowda V, Dixit S, et al. Prevalence of New Onset Anosmia in COVID-19 Patients: Is The Trend Different Between European and Indian Population? Ind J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2020; 72(4):484-87. doi: 10.1007/s12070-020-01986-8.

doi: 10.1007/s12070-020-01986-8 |

| 9. | American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. Anosmia, hyposmia, and dysgeusia symptoms of coronavirus disease. Available from https://www.entnet.org/content/aao-hns-anosmia-hyposmia-and-dysgeusia-symptomscoronavirus-disease. Accessed May 1, 2020. |

| 10. |

Lechner M, Chandrasekharan D, Jumani K, et al. Anosmia as a presenting symptom of SARS-CoV-2 infection in healthcare workers-a systematic review of the literature, case series, and recommendations for clinical assessment and management. Rhinology 2020; 58(4):394-9. doi: 10.4193/Rhinzo.189.

doi: 10.4193/Rhin20.189 pmid: 32386285 |

| 11. | US CfDCa. Symptoms of COVID-19. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html. Accessed April 17, 2020. |

| 12. |

Xu H, Zhong L, Deng J, et al. High expression of ACE2 receptor of 2019-nCoV on the epithelial cells of oral mucosa. Int J Oral Sci 2020; 12(1):8. doi: 10.1038/s41368-020-0074-x.

doi: 10.1038/s41368-020-0074-x |

| 13. |

Sungnak W, Huang N, Bécavin C, et al. SARS-CoV-2 entry factors are highly expressed in nasal epithelial cells together with innate immune genes. Nat Med 2020; 26(5):681-7. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0868-6.

doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0868-6 |

| 14. |

Geurkink N. Nasal anatomy, physiology, and function. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1983; 72(2):123-128.

doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(83)90518-3 |

| 15. |

Brann DH, Tsukahara T, Weinreb C, et al. Non-neuronal expression of SARS-CoV-2 entry genes in the olfactory system suggests mechanisms underlying COVID-19-associated anosmia. Sci Adv 2020; 6(31):eabc5. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.25.009084.

doi: 10.1101/2020.03.25.009084 |

| 16. |

Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet (London, England) 2020; 395(10224):565-74. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30251-8.

doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30251-8 |

| 17. |

Jahanshahlu L, Rezaei N. Central nervous system involvement in COVID-19. Arch Med Res. 2020; 51:721-2. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2020.05.016.

doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2020.05.016 pmid: 32471704 |

| 18. |

Saghazadeh A, Rezaei N. Towards treatment planning of COVID-19: Rationale and hypothesis for the use of multiple immunosuppressive agents: Anti-antibodies, immunoglobulins, and corticosteroids. Int Immunopharmacol 2020; 84(106560):1-6. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106560.

doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106560 |

| 19. | Yazdanpanah N, Saghazadeh A, Rezaei N. Anosmia: a missing link in the neuroimmunology of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Rev Neurosci 2020; 1. |

| 20. |

Bunyavanich S, Do A, Vicencio A. Nasal gene expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in children and adults. JAMA 2020; 323(23):2427-9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8707.

doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8707 pmid: 32432657 |

| 21. |

Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 2020; 181(2):271-80.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052.

doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052 |

| 22. |

Boesveldt S, Postma EM, Boak D, et al. Anosmia: A clinical review. Chem Senses 2017; 42(7):513-23. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjx025.

doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjx025 pmid: 28531300 |

| 23. |

Moran DT, Jafek BW, Eller PM, et al. Ultrastructural histopathology of human olfactory dysfunction. Microscopy Res Tech 1992; 23(2):103-110.

doi: 10.1002/jemt.1070230202 |

| 24. |

Galougahi MK, Ghorbani J, Bakhshayeshkaram M, et al. Olfactory bulb magnetic resonance imaging in SARS-CoV-2-induced anosmia: the first report. Acad Radiol 2020; 27(6):892-3. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2020.04.002.

doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2020.04.002 |

| 25. |

Chetrit A, Lechien JR, Ammar A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of COVID-19 anosmic patients reveals abnormalities of the olfactory bulb: Preliminary prospective study. J infect 2020; 81(5):816-46. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.07.028.

doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.07.028 |

| 26. |

Girardeau Y, Gallois Y, De Bonnecaze G, et al. Confirmed central olfactory system lesions on brain MRI in COVID-19 patients with anosmia: a case-series. medRxiv 2020; 2020.2007.2008.20148692. doi: 10.1101/2020.07.08.20148692.

doi: 10.1101/2020.07.08.20148692 |

| 27. |

Klironomos S, Tzortzakakis A, Kits A, et al. Nervous System Involvement in COVID-19: Results from a Retrospective Consecutive Neuroimaging Cohort. Radiology 2020; 202791. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020202791.

doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020202791 |

| 28. |

Altundag A, Yıldırım D, Sanli DET, et al. Olfactory cleft measurements and COVID-19-related anosmia. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2021; 164(6):1337-44. Epub 2020 Oct 13. doi: 10.1177/0194599820965920.

doi: 10.1177/0194599820965920 |

| 29. |

Eliezer M, Hamel AL, Houdart E, et al. Loss of smell in COVID-19 patients: MRI data reveals a transient edema of the olfactory clefts. Neurology 2020; 95(23):e3145-e3152. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010806.

doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010806 |

| 30. |

Niesen M, Trotta N, Noel A, et al. Structural and metabolic brain abnormalities in COVID-19 patients with sudden loss of smell. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2021; 48(6):1890-901. doi: 10.1007/s00259-020-05154-6.

doi: 10.1007/s00259-020-05154-6 |

| 31. |

Kandemirli SG, Altundag A, Yildirim D, et al. Olfactory bulb MRI and paranasal sinus CT findings in persistent COVID-19 anosmia. Acad Radiol 2021; 28(1):28-35. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2020.10.006.

doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2020.10.006 pmid: 33132007 |

| 32. |

Aragão MFVV, Leal MC, Cartaxo Filho OQ, et al. Anosmia in COVID-19 associated with injury to the olfactory bulbs evident on MRI. Am J Neuroradiol 2020; 41(9):1703-6. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A6675.

doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A6675 pmid: 32586960 |

| 33. |

Brookes NRG, Fairley JW, Brookes GB. Acute olfactory dysfunction—A primary presentation of COVID-19 infection. Ear Nose Throat J 2020; 99(9):94-8. doi: 10.1177/0145561320940119.

doi: 10.1177/0145561320940119 |

| 34. |

Coolen T, Lolli V, Sadeghi N, et al. Early postmortem brain MRI findings in COVID-19 non-survivors. Neurology 2020; 95(14):e2016-e2027. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010116.

doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010116 |

| 35. |

Gane SB, Kelly C, Hopkins C. Isolated sudden onset anosmia in COVID-19 infection. A novel syndrome? Rhinology 2020; 58(3):299-301. doi: 10.4193/rhin20.114.

doi: 10.4193/Rhin20.114 pmid: 32240279 |

| 36. |

Naeini AS, Karimi-Galougahi M, Raad N, et al. Paranasal sinuses computed tomography findings in anosmia of COVID-19. Am J Otolaryngol 2020; 41(6):102636. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2020.102636.

doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2020.102636 |

| 37. |

Butowt R, Bilinska K. SARS-CoV-2: Olfaction, brain infection, and the urgent need for clinical samples allowing earlier virus detection. ACS Chemical Neuroscience 2020; 11(9):1200-1203. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00172.

doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00172 pmid: 32283006 |

| 38. |

Jalessi M, Barati M, Rohani M, et al. Frequency and outcome of olfactory impairment and sinonasal involvement in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Neurol Sci 2020; 41(9):2331-8. doi: 10.1007/s10072-020-04590-4.

doi: 10.1007/s10072-020-04590-4 pmid: 32656713 |

| 39. |

Eliezer M, Hautefort C, Hamel AL, et al. Sudden and complete olfactory loss function as a possible symptom of COVID-19. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2020; 146(7):674-5. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.0832.

doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.0832 |

| 40. |

Cooper KW, Brann DH, Farruggia MC, et al. COVID-19 and the chemical senses: supporting players take center stage. Neuron 2020; 107(2):219-33. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.06.032.

doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.06.032 |

| 41. |

Trotier D, Bensimon JL, Herman P, et al. Inflammatory Obstruction of the Olfactory Clefts and Olfactory Loss in Humans: A New Syndrome? Chemi Senses 2007; 32(3):285-92. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjl057.

doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjl057 |

| 42. |

Han AY, Mukdad L, Long JL, et al. Anosmia in COVID-19: mechanisms and significance. Chem senses 2020; 45(6):423-8. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjaa040.

doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjaa040 |

| 43. |

Gu J, Gong E, Zhang B, Zheng J, Gao Z, Zhong Y, et al. Multiple organ infection and the pathogenesis of SARS. J Experi Med 2005; 202(3):415-24. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050828.

doi: 10.1084/jem.20050828 |

| 44. |

Cao Y, Li L, Feng Z, Wan S, et al. Comparative genetic analysis of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV/SARS-CoV-2) receptor ACE2 in different populations. Cell discovery 2020; 6(1):1-4. doi: 10.1038/s41421-020-0147-1.

doi: 10.1038/s41421-020-0147-1 |

| 45. |

Rombaux P, Mouraux A, Bertrand B, et al. Olfactory function and olfactory bulb volume in patients with postinfectious olfactory loss. The Laryngoscope 2006; 116(3):436-9. doi: 10.1097/01.MLG.0000195291.36641.1E.

doi: 10.1097/01.MLG.0000195291.36641.1E |

| 46. |

Mueller A, Rodewald A, Reden J, et al. Reduced olfactory bulb volume in post-traumatic and post-infectious olfactory dysfunction. Neuroreport 2005; 16(5):475-8. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200504040-00011.

doi: 10.1097/00001756-200504040-00011 pmid: 15770154 |

| 47. |

Laurendon T, Radulesco T, Mugnier J, et al. Bilateral transient olfactory bulb edema during COVID-19-related anosmia. Neurology 2020; 95(5):224-5. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009850.

doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009850 pmid: 32444492 |

| 48. |

Zheng J, Wong LYR, Li K, et al. COVID-19 treatments and pathogenesis including anosmia in K18-hACE2 mice. Nature 2021; 589(7843):603-7. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2943-z.

doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2943-z |

| 49. |

Whitcroft KL, Hummel T. Olfactory Dysfunction in COVID-19: Diagnosis and Management. JAMA 2020; 323(24):2512-4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8391.

doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8391 |

| 50. |

Lechien JR, Chiesa-Estomba CM, De Siati DR, et al. Olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions as a clinical presentation of mild-to-moderate forms of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a multicenter European study. Eur Archives Oto-Rhino-Laryngol 2020; 277(8):2251-61. doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-05965-1.

doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-05965-1 |

| 51. |

Touisserkani SK, Ayatollahi A. Oral corticosteroid relieves post-COVID-19 anosmia in a 35-year-old patient. Case Rep Otolaryngol 2020; 2020:5892047. doi: 10.1155/2020/5892047.

doi: 10.1155/2020/5892047 |

| 52. |

Tanasa IA, Manciuc C, Carauleanu A, et al. Anosmia and ageusia associated with coronavirus infection (COVID-19)- what is known? Experi Thera Med 2020; 20(3):2344-7. doi: 10.3892/etm.2020.8808.

doi: 10.3892/etm.2020.8808 |

| [1] | 徐佳, 王萱, 金征宇, 王勤, 游燕, 王士阗, 钱天翼, 薛华丹. 探索应用延长至50分钟的钆赛酸二钠增强磁共振T1 Maps评价大鼠肝纤维化模型肝功能的价值:延长的肝胆期可能提供帮助[J]. Chinese Medical Sciences Journal, 2021, 36(2): 110-119. |

| [2] | 王雪丹, 王世伟, 王波涛, 陈志晔. 磁共振场强对脑T2-FLAIR图像纹理特征影响的初步研究[J]. Chinese Medical Sciences Journal, 2020, 35(3): 248-253. |

| [3] | 王波涛, 刘明霞, 陈志晔. 磁共振T2加权成像纹理特征分析在脑胶质母细胞瘤与脑原发性中枢神经系统淋巴瘤鉴别诊断中的价值[J]. Chinese Medical Sciences Journal, 2019, 34(1): 10-17. |

| [4] | 徐佳, 王萱, 金征宇, 游燕, 王勤, 王士阗, 薛华丹. 钆塞酸二钠增强磁共振图像纹理分析对于评价大鼠肝纤维化的价值[J]. Chinese Medical Sciences Journal, 2019, 34(1): 24-32. |

| [5] | 王波涛, 樊文萍, 许欢, 李丽慧, 张晓欢, 王昆, 刘梦琦, 游俊浩, 陈志晔. 磁共振扩散加权成像纹理特征分析在乳腺良恶性肿瘤鉴别中的价值[J]. Chinese Medical Sciences Journal, 2019, 34(1): 33-37. |

| [6] | 李平, 朱亮, 王萱, 薛华丹, 吴晰, 金征宇. 影像学诊断1例III型胆总管囊肿[J]. Chinese Medical Sciences Journal, 2018, 33(3): 194-203. |

| [7] | 陈志晔, 刘梦琦, 于生元, 马林. 多参数磁共振成像诊断小脑血管母细胞瘤1例报告[J]. Chinese Medical Sciences Journal, 2018, 33(3): 188-193. |

| [8] | 陈志晔, 刘梦琦, 马林. 延髓发病型及脊髓发病型肌萎缩侧索硬化症患者皮层变薄模态:基于表面的形态学研究[J]. Chinese Medical Sciences Journal, 2018, 33(2): 100-106. |

| [9] | 李丽慧, 黄厚斌, 陈志晔. 对比增强T2-FLAIR早期诊断复发性视神经炎一例报告[J]. Chinese Medical Sciences Journal, 2018, 33(2): 130-134. |

| [10] | 陈志晔,刘梦琦,马林. 延髓发病型及脊髓发病型肌萎缩侧索硬化症脑部磁共振结构特征变化[J]. Chinese Medical Sciences Journal, 2018, 33(1): 20-28. |

| [11] | 刘梦琦, 陈志晔, 马林. 三维伪连续动脉自旋标记序列的可重复性:不同功能状态的健康成人在不同标记时间的脑容积灌注成像[J]. Chinese Medical Sciences Journal, 2018, 33(1): 38-44. |

| [12] | 陈志晔, 刘梦琦, 马林. 基于表面的形态测量学:3T与7T高分辨磁共振结构成像受试者内比较[J]. Chinese Medical Sciences Journal, 2017, 32(4): 226-231. |

| [13] | 潘海鹏, 劳群, 费正华, 杨丽, 周海春, 赖灿. MR淋巴管造影诊断婴儿乳糜胸一例及文献回顾[J]. Chinese Medical Sciences Journal, 2017, 32(4): 265-268. |

| [14] | 陈志晔, 臧秀娟, 刘梦琦, 刘梦雨, 李金锋, 谷昭艳, 马林. 16例新发2型糖尿病患者脑部皮层厚度异常变化的MRI初步研究[J]. Chinese Medical Sciences Journal, 2017, 32(2): 75-82. |

| 阅读次数 | ||||||

|

全文 |

|

|||||

|

摘要 |

|

|||||

|